Charlotte McCurdy

The Tech We Feel Most

Gossypium hirsutum:

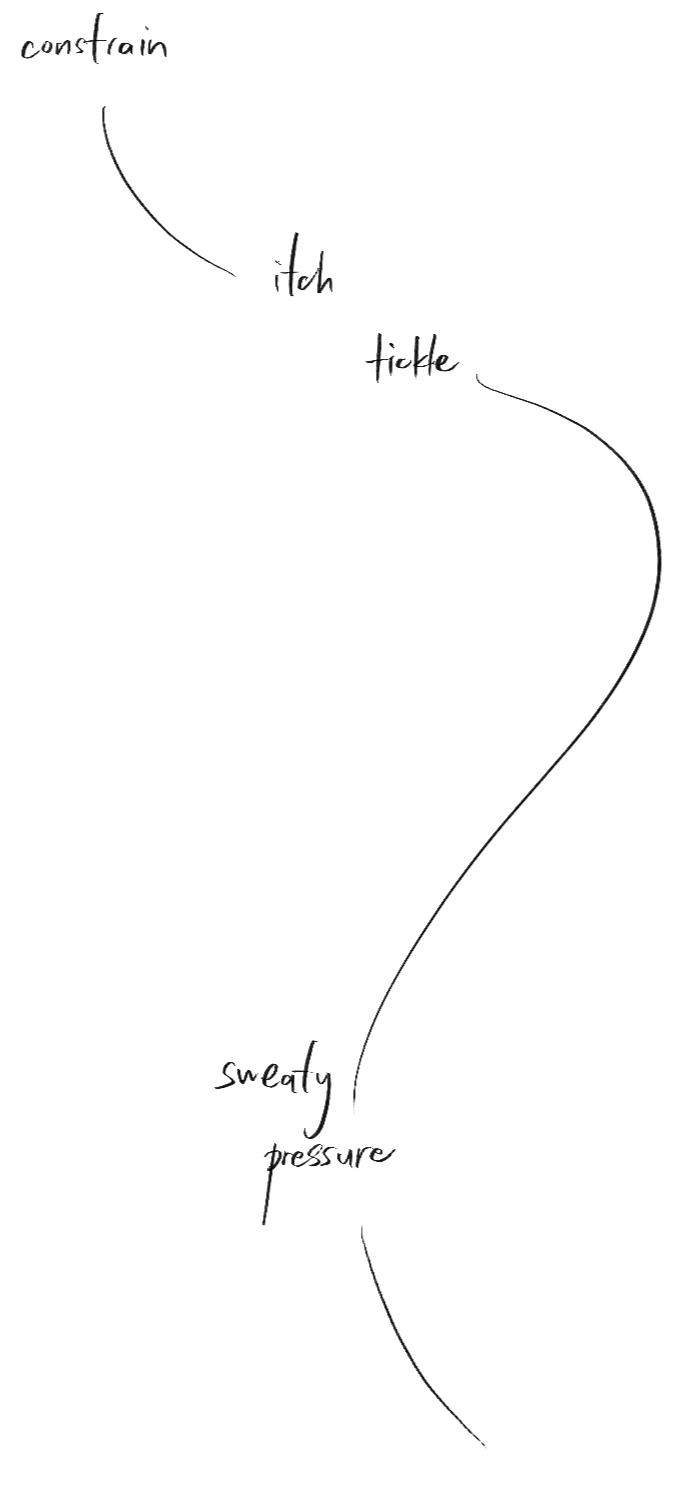

constrain - itch - tickle - support - caresse - sweaty - pressure - give - stretch - resist - rough - strong - smooth - warm - hot - protected - exposed - enveloped - soothed - hugged

It's June and humid—more humid than anywhere I have tried to work before—which means surprises. I need to pour six good test sheets today if I am going to keep my timeline. I flip on the induction hot plate under the 10-gallon kettle I am using as a water bath; this will make the space even muggier. That click starts the clock on the familiar flow of a working session.

I label eight glass beakers with their unique, ever-climbing ID numbers. I check the plan I laid out the night before on a sticky note and then weigh powders on a digital scale, and measure liquids with a pipette. I combine it all with a handheld immersion blender. By the fifth beaker, the vibrations numb my hand. Shelves around me brim with rows of small glass jars from past experiments—most of them dead ends.

Soon these liquids will become sheets of algae-based textiles—proofs-of-concept that carbon can be sequestered in fabric. The sheets will be so thin, so light, and so translucent that they’ll be nearly immaterial. Less than objects. Hypoobjects. Each will only store a few grams of carbon, but they will be something you can touch.

When you consider it, textiles are undoubtedly the technology we feel the most throughout our lives and days. They offer our bodies the most sensation. After all, we’re almost always enveloped in fabric—swaddled, dressed, or in bed. But with the omnipresence of screens, we lose sight—or in this case touch—of a technology that humans have been developing for more than 30,000 years, a technology with which we’ve biologically co-evolved, an influence evident in our body hair, sweat, and fine motor skills honed partly to make knots, sew with needles, and spin thread.

The common trope in meditation of “notice your breathing” could have been “notice your skin touching your clothes.” In the vernacular sense of “Technology!” textiles perhaps lack speedy, metallic power. There is a domesticity that makes them seem banal.

Putting aside the fact that “textile” and “technology” share the same Indo-European etymological root teks (meaning to weave or fabricate), perhaps it is uncomfortable to apply contemporary associations attached to technology to textiles precisely because the clothes we wear are too closely intertwined with our humanity. Distinct from the technologies that become normalized through familiarity, textiles are viscerally part of our own humanness.

2035 will mark the centenary of the first fully petrochemical textile—nylon. We did not co-evolve with synthetic materials—at least we haven’t yet. In the short span of time since Wallace Carothers set off a materials revolution based on polymers, synthetics have grown to represent two-thirds of global textile production. We’ve traded plants and hides for fossil fuels. My hunch and hope is that by making algal textiles, I can re-technologize fabrics, and in doing so make visible that the globe-spanning impacts of today’s industrial textile production are not inherently necessary.

Polyethylene terephthalate:

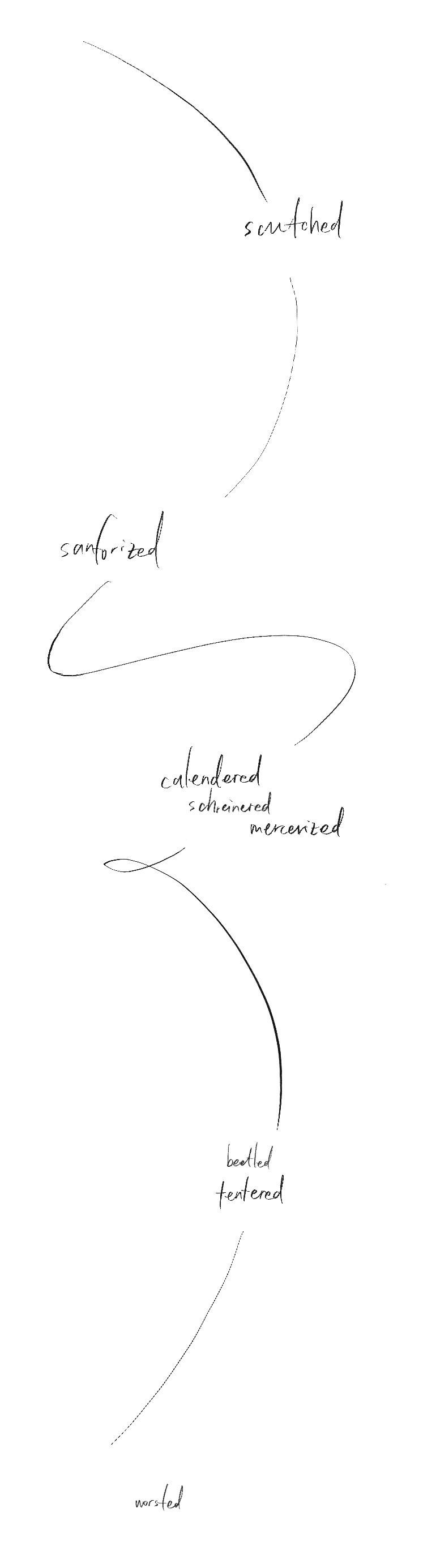

scutched - tattersall - sanforized - calendered - schreinered - mercerized - beetled - lawn - tentered - rapier - azoic - latigo - denier - tricot - faille - shantung - batiste - gabardine - worsted

Scutched, sanforized, calendered, schreinered, mercerized, beetled, tentered, worsted—the vocabulary of textiles speaks to centuries of accumulated knowledge and technique contained in a simple shirt. Yet another reason textiles still fit uncomfortably into the generic silhouette of “technology” might be gender.

I feel ambivalent about being a woman who went to graduate school for industrial design and then got pulled into textiles and fashion. That said, I have always been drawn to fabric. My grandmother made clothes for my mother, and when I was seven, I was given her Bernina sewing machine, which is such a tank that it still commands a decent resale price. As soon as I was old enough to be in charge of my own Halloween costumes, I became annually impractically swathed. One year, I covered myself in a trailing mass of red fabric. When asked what I was dressed as, I dramatically responded, “Death!”

As I grew up, I started tailoring my own clothes, and by my teens I was bewitched by the transformations that fabric allows, working in my school’s costume shop and taking night classes at the Fashion Institute of Technology. The magic of patternmaking—of flat sheets aligning at edges of mismatched curves to form 3D compound shapes—activated my brain in the way puzzles do. Add to that the grace of the bias in a weave, and a next order of curvature emerges to blend the lines of a surface.

This way of thinking about crafting fabrics was inflected by my love of calculus at the time. In the same way that integration and derivation can suck your mind through different dimensions of interrelated forms, patternmaking moves through similar abstracted logics as it slides from 2D to 3D and then dances through time as the body flexes and glides.

Ovis aries

speed - caution - epiphany - delight - disappointment - despair - frustration - focus - flow - determined - organized - overwhelmed - impatient - hopeless - exposed - afraid

Two computer-controlled cutting machines set the hypnotic rhythm of the space where I work. Their whining stepper motors translate digital-to-physical. They are cutting sheets of the fully cured sheets into test sequins. Onscreen, I tweak control points, place edges and curves within grids of sequentially modified forms. I calculate concentrations and volumes to plan the next tests.

In the morning, a three-foot sheet of material greets me with an s-crack slicing across its width. My stomach drops with familiar dread. The crack feels like an indictment of my competence.

I try not to imagine disappointed collaborators and public embarrassment as I cut usable sections from the larger piece, place the scraps in storage for future tests, and reset the mold for another attempt. As the project transitions from a personal materials exploration into the shared, public, finished thing, fear ratchets up.

There's always the background anxiety—will I meet deadlines, will they come out just right, can I execute what I've promised? Then there's the existential weight of climate work itself. But the third, more personal fear is the fear of being seen: the fear of being misunderstood or found disappointing.

This introversion is perverse because a core goal of my work is to make tools for thinking and talking about climate that welcome large audiences. Some of the most significant challenges of fighting for the climate are not technological, but social. Yet a personal fear of the social consistently sabotages me. The flow state in the studio gives way to anxiously imagining. But it is not about stage fright.

My therapist once watched a video of me giving a talk and asked, "Who is that person?" She didn't recognize the fearless authenticity of the version of me who gets to be absorbed in connecting a constellation of ideas. Yet this confident aspect evaporates when in smaller groups of strangers or the early days of collaboration. When I go to conferences, I'm generally so overwhelmed I hide whenever I can.

So I repeat a personal mantra: "do it for the work." My discomfort is nothing if I truly believe that what I am making could have a positive impact. Moving towards the discomfort is how I will feel my way through the darkness of uncertainty.

It's quiet as I jog the large curved sequins into alignment like small decks of cards. I fan each deck while using a pin to poke clear the tiny cut circular holes that the embroiderer will use to hand-sew these embellishments onto a one-of-a-kind dress. Tomorrow, I will meet a collaborator on a New York City sidewalk, hand over weeks of work, and hope that it is enough. I will try to freeze this moment in my mind: the quality of the light, the temperature of the air, and the complete improbability of being where I am, doing what I’m doing.

Textiles are the technology we feel most. Ever-present at the boundary of our bodies and the world, they are the technology that most allows us to feel ourselves, to experience our edges and embodiedness. Textiles let us feel our feelingness. And maybe, if we can really notice them again, we can change them for the better.

Notice where your clothes touch your skin.

The work described in the essay was part of a 2021 collaboration with fashion designer Phillip Lim. The resulting Algae Sequin Dress was included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's 2024 Costume Institute exhibition "Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion" and is now part of the Met's permanent collection, making McCurdy among the youngest people to have had work acquired by the museum.

Charlotte McCurdy

Charlotte McCurdy is Core Design Lecturer at Stanford University's d.school, where she teaches design at the intersection of sustainability, materials, and culture. She conducts design research by developing novel material systems that address the societal and environmental implications of manufacturing. She is the recipient of the 2025 Biodesign Challenge Outstanding Instructor Award, the FastCompany 2019 Linda Tischler Memorial Award, and was named a "25 for 2025 World Design Congress Trailblazer" by The Design Council. Originally from New York City, she now lives in San Francisco with her husband David and their dog.