Alison McCook

Friggles the Frog

As a young science journalist, my first reporting assignment consisted of finding out how to kill my pet frog. I’m not a sadist. Let me explain. To tell the story of Friggles, let’s go back to my lonely childhood. I had no siblings and my parents both worked into the night, and so for years, I begged—begged—for a pet. Any pet.

Finally, in elementary school, they caved. But my parents didn’t take me to a shelter to meet a puppy who would leap all over me and lick my face. No, we went to a toy store—my mother handed over a few dollar bills for a Grow-A-Frog. We bought a tank, a pump, and gravel, and a few weeks later, a box arrived at our house outside Philadelphia (addressed to me!). Inside was a tadpole, a couple of inches long, squirming against the sides of a small, clear bag filled with water.

Looking back, I see how unusual my first pet experience was. But my parents were unphased—my dad grew up with a rabbit that shared his bed and a parakeet that perched on the bow of his violin while he practiced scales. To him, a mail-order tadpole was no big thing.

Plus, the Grow-A-Frog was supposed to be educational—over time, the tadpole would transform, sprout little arms and legs, and teach me the amazing process of metamorphosis. For some kids, it could spark a lifelong fascination with nature’s wonders; it certainly did for me, and likely inspired my decision to write about science for a living.

Initially, it looked like my first experience with the wonders of nature would be short-lived. The squirmy tadpole I was so excited to nurture into adulthood stopped moving soon after it arrived. Its replacement was DOA—the lifeless body bobbing in the water.

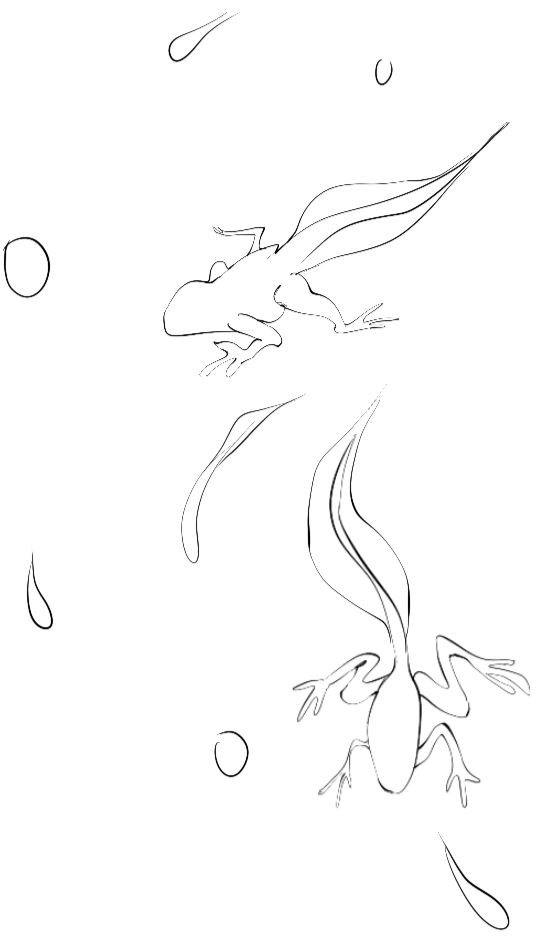

Livid, my mother got on the phone with the company and told them that they had traumatized her only child (an exaggeration) and they needed to send us their healthiest frog. Immediately. That’s when Friggles arrived, and I got to experience the metamorphosis I’d been promised.

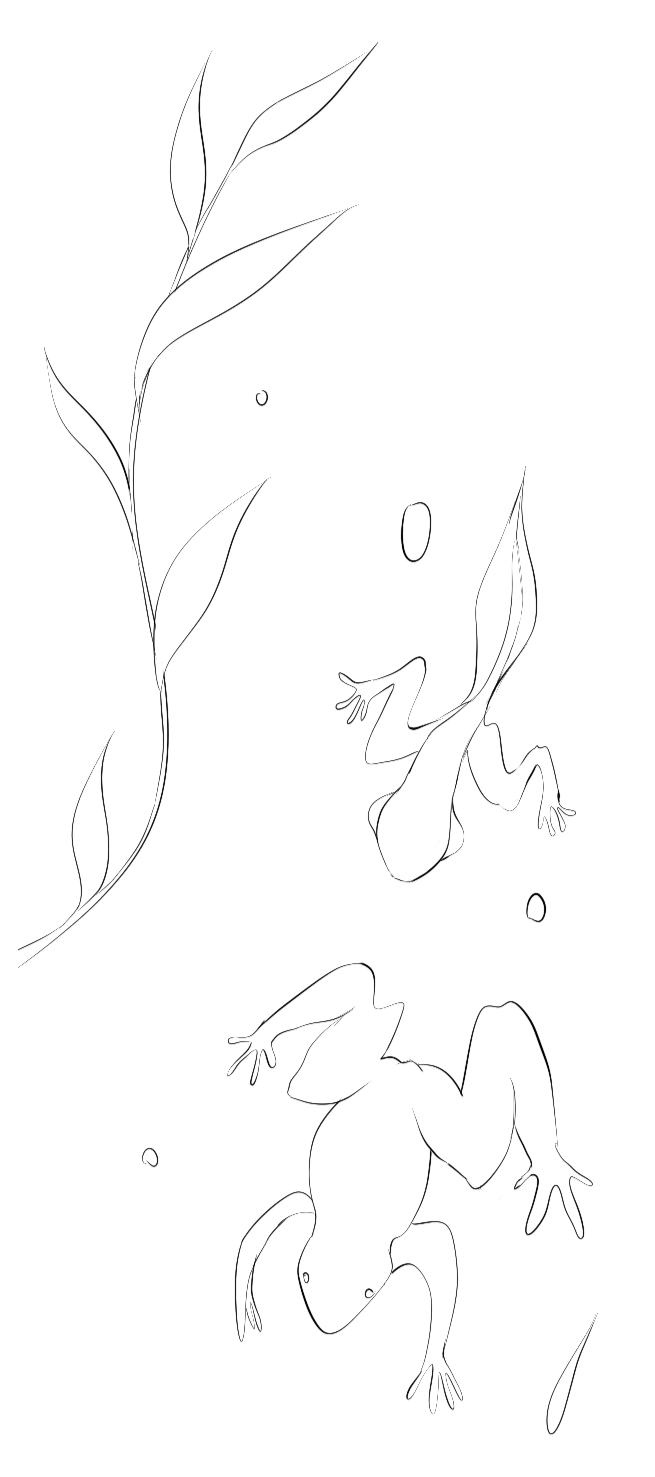

Over time, Friggles’s body went from a bulb with a clear, quivery tail to a streamlined, underwater frog, sprouting little arms and legs with black nails. I spent hours watching him, observing how he spent his days. Mostly, he sat on the floor of his tank, occasionally bobbing to the surface for air, and rarely sprinting in circles along the perimeter in bursts of activity, then floating calmly back to the bottom. He sang for the first time on Christmas morning, a low, continuous vibration. My parents and I tried to guess why and when he would do it again. (He did, many times, but never when any of us had predicted.)

Earlier this year, I reached out to a representative of the company, which is still in business, who told me Friggles was most likely an African clawed frog, which can live up to 15 years. Today, they sell smaller species from the clawed frog family known as Pipidae, which the rep said has an average lifespan of 5 years.

My mother and I spent years dropping thousands of food pellets into Friggles’s tank. I was always too nervous to clean his water, so once a month, she bravely scooped him out and scrubbed away the scum and stink.

She was determined to keep him happy, and he was determined to survive. Sometimes his slimy body would slip through her fingers and drop several feet onto the floor, or even down the garbage disposal. She just scooped him back up, and all was well.

I never stopped asking for pets, and Friggles eventually met a rabbit, a fish, two birds, two dogs, and two cats.

But they say you never forget your first, and Friggles often stole the show. He became the unofficial mascot of our household, and my mother began adding frog tchotchkes to the interior and exterior decor. He won a pet contest at my school (in the “miscellaneous” category). He was the subject of many running jokes, as my dad imitated the shocked Grow-A-Frog employees who couldn’t believe my mom was calling again to order more food for the same animal. We marked Friggles’s birthday on the calendar; one year we considered throwing him a surprise party. Friends, relatives, even my teachers asked about him, . “How’s Friggles? Is he still alive?”

Friggles saw me through elementary, middle, and high school, and sent me off to college in Montreal. There, I studied animals (biology) and writing (English), and upon graduation got a job as a medical writer.

One day, my mother called me at work, something she never did. “Friggles is sick,” she told me. Apparently, his body was swelling up; she said he looked like a frog balloon with a tiny head, little arms and legs. The vet she used for our other animals didn’t know about frogs and refused to euthanize him. “I need help,” my mother said.

This was 1998, when the internet offered little information. And this was Friggles—I didn’t trust the ramblings of someone online. So I picked up the phone and started making calls. I found amphibian experts who confirmed that Friggles was likely dying, but they didn’t know how best to humanely put him down. Each person referred me to someone else. And after a few tries, I found someone who knew what to do: put Friggles in a small cup of water, place him in the refrigerator for 20 minutes, then transfer him to the freezer. The cold of the refrigerator would slow his body in a way that would feel like falling asleep, the expert reassured me; the freezer would kill him and he wouldn’t feel a thing.

Soon after that, I sat on the phone with my mother, talking her through the steps. She wanted me there for support when she moved him, with tears in her eyes, from the refrigerator to the freezer. “I can’t believe it’s over,” she said. Not everyone felt the loss so deeply: my dad was upstairs playing video games.

On the day he died, Friggles was 18 years old.

Yes, we killed him. And I felt sad. But I’d built a full life for myself in the 18 years since Friggles arrived, and I was relieved that we could give him a (hopefully) compassionate sendoff. At my medical writing job, I spent days reviewing anatomy and physiology textbooks, thinking of new ways to describe something that had been described a million times before: the human cardiovascular system. When Friggles got sick, there was no textbook to tell us how to help. Instead, I had to find out the information myself, call experts in the field, and ask questions. Scientists helped me better understand the creature I’d spent my childhood observing and wondering about. They explained what the cold of the fridge and freezer would likely do to his physiology. It was my first taste of journalism.

Shortly after Friggles died, I applied to a master’s program in science journalism. Now, I regularly call experts in all different fields who tell me about what they’ve spent their lives wondering about and observing. It is a privilege to talk to scientists about cutting-edge ideas and results not yet in textbooks.

My mom died almost 10 years after Friggles. At her funeral, her best friend told the story of Friggles. Not because he was so incredible (which he was), but because he showed us all how incredible my mother was—the fierce love for her daughter that made her give in and get a household pet, then care for said animal for nearly two decades, long after her daughter grew up.

In 2019, I took my preschool-aged daughter to our local garden store where we picked out five chirping balls of fluff that became our chickens. Over the next few months, she watched them grow crowns and shed their fluff for feathers, and heard their “cheeps” mature into “clucks.” When one died after only a few days, we buried her in the backyard under a painted rock.

Chickens aren’t friendly like dogs and cats, but they’re fun to look at. My daughter and I watch them circle their pen, I explain to her about “pecking order,” and we discuss who is in charge when, since the hierarchy seems to be ever-changing. We observe, make hypotheses, and continue observing to see if our ideas hold up. And the eggs are delicious.

She and I also talk about Friggles, 20 years after his death. I tell my daughter about how angry my mom got when we kept receiving sick tadpoles, and how she made sure I got a healthy frog. He was so healthy, she ended up having to take care of him for longer than anyone expected. I hope my daughter sees what I see: that the world is full of amazing creatures that can surprise and inspire us, and that good parents will do whatever they can to give their kids happy, interesting lives.

Alison McCook

Alison McCook is a writer living outside Philadelphia. She has spent most of her career in science journalism, writing and editing articles about new research and what it means. Her work has appeared in publications including Reuters, Scientific American, Undark, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Knowable, Nature, and Science. She spent several years as the editor of Retraction Watch, conducting investigative journalism that focused on academia, publishing, and scientific misconduct. She has four chickens and a needy cat.